Trauma, Power, and the Use of the Kyosaku in American Zen

By Brandon Dean Lamson

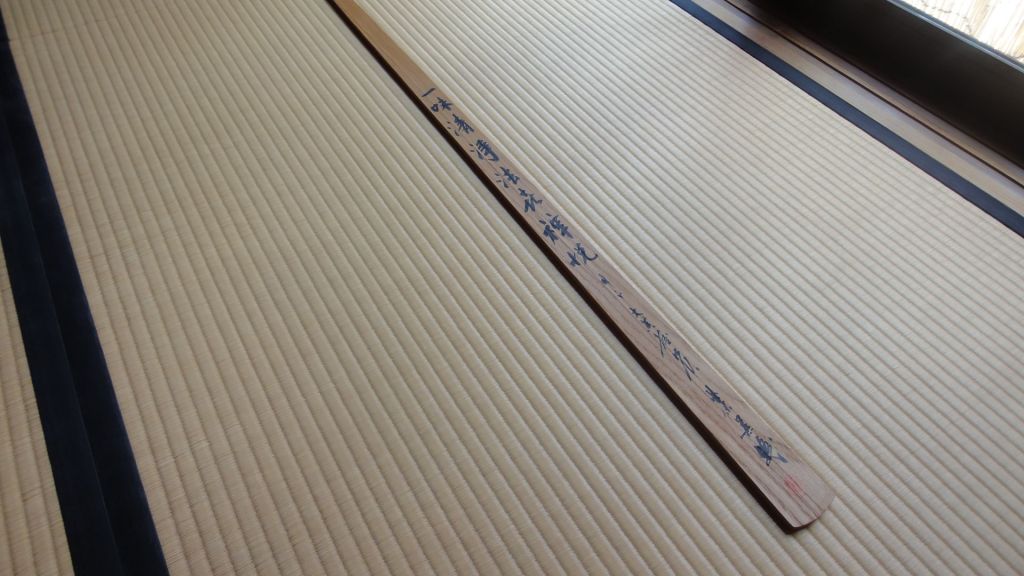

“Thwack, thwack!”As the sound of wood slapping flesh reverberated through the zendo, I turned toward the source of the noise, seeing one of the monitors poised behind someone and raising a wooden stick the length of a baseball bat. He brought the stick, called the kyosaku, swiftly down on the person’s shoulders as she held her hands in gassho. Suddenly, defying my training in stillness, I unfolded my legs and rose from my seat, exiting the zendo and walking swiftly down the stone monastery stairs as I strode through the doors and onto the summer lawn deep in shadow. Breathless, I paced through the cool grass.

My heart thudded in my chest, and I felt lightheaded and nauseous. “They should have said something; they should have warned us.” I repeated over and over. The shadows on the lawn lengthened as the sun descended toward the soft outlines of the Catskills. I felt trapped, knowing that it would be difficult for me to leave, especially after nightfall. I was hundreds of miles from home, and a long bus ride had brought me here from the city.

Several minutes later, the other monitor who hadn’t wielded the stick found me pacing on the lawn. She approached, circling toward me in her black robes, and I stopped and told her what was happening as best I could, grasping for words through the haze clouding my mind, a feeling of disorientation familiar to those who struggle with trauma. She listened without judgment, her blue eyes searching my face, and I began to calm down. She asked me whether we’d been informed about the kyosaku during our orientation the night before. We had not. Apparently the monk who had given us the orientation had forgotten to mention it. The use of the stick had been a complete surprise to me and to the other new residents.

After telling me that receiving the kyosaku was always voluntary and that people had to request it, she encouraged me to return to the zendo before the evening liturgy so I could participate in the chanting. I did not want to re-enter that space but I forced myself to, hoping that it would bring me some sense of peace or of closure now that I knew that blows from the stick were optional. Still, my body did not feel composed. My fluttering stomach, the heat flushing my face, and a feeling of heaviness in my arms and legs persisted. Even the chanting, which I usually found soothing, did not bring me ease.

The use of the kyosaku reputedly began in Chinese Zen monasteries near the end of the Tang dynasty. In Japanese Zen it has been a common part of the tradition, and its purpose is to encourage wakefulness during long periods of zazen such as sesshins. For this reason it is often called in English “the encouragement stick.” Used properly, the kyosaku can rouse the energy of fatigued practitioners and bring their awareness back to their bodies. The strike of the kyosaku is intended to focus the mind on one’s present moment experience by stimulating acupressure points on the upper back. Doing this well requires some degree of skill on the part of the person wielding the stick.

One dynamic question that the kyosaku raises in American Zen practice is what exactly are we importing from Japanese cultural and religious traditions, and why? What traditional Japanese practices should be discarded as inappropriate and unskillful in our twenty first century American context, and what should we preserve or modify? How can we reinvent and enliven our practice in ways that reflect our contemporary moment, despite the pull to perpetuate inherited rituals and ceremonial forms that may cause unnecessary suffering?

Throughout its history, Buddhism has been characterized by its ability to adapt to the various social and cultural environments where it flourished. I could not help noticing that most often the stick was wielded by white men serving as monitors, and that it had been brought to American Zen by Japanese male teachers. In our current social moment of reckoning with the abuses of patriarchy, the vision of these men striking their students was disturbing and compelled me to examine my own identity. I was drawn to the macho culture in Zen practice, the ethos of enduring hardship without complaint and of striving to break through or penetrate delusion in order to attain awakening. The masculine tone of these metaphors appealed to me in a way that I could not identify, and the notion of spiritual toughness accorded with messages I was given about what it meant to be a man.

In the summer of 2019, I had signed up for a one month residential stay at a Zen monastery in upstate New York. Before my arrival, I had a phone interview with the same monk who’d later find me after I’d fled the zendo. I was also sent a 22 page application form that included questions about addiction, mental illness, and trauma history as well a detailed description of practice at the monastery. Nowhere was the use of the kyosaku mentioned.

The question on the application about trauma read, “Do you have any history of trauma?Please describe briefly to the degree that you are comfortable. Include how this impacts your daily life.” I responded, “I have a history of trauma, but it does not interfere with my daily life or with my practice of the dharma.” Clearly, the wording of these questions missed something vital, namely an acknowledgment of how the use of the stick could be severely triggering for anyone who has survived trauma. If I had been more fully informed, my answer would have been very different.

Once I realized what I was dealing with, I attempted to approach it as an opportunity for practice. I spoke with monastics about my issues with the stick, and sought collaborative solutions. One person asked me if I’d ever been hit with the stick myself, implying that if I only allowed myself to experience it, then it wouldn’t bother me anymore. Another told me that she did not have much sympathy, and minutes later apologized for being insensitive. Yet another suggested that I speak to one of the senior monastics and request that they suspend the use of the kyosaku entirely during my stay. Although these folks intended to support me, their understanding of trauma varied and the impact of their words did not always coincide with their intention.

My general sense was that there was debate within the community about using the kyosaku, and that most of the monastics wanted to preserve it because it was one of the traditional practice forms passed down to them by their former teacher. While I understood this view, I had to weigh that feeling against the damage the use of the kyosaku would inflict on all of the future students who would come to the monastery. The omission of any mention of the kyosaku on either the monastery website or in its application materials was troubling. When I suggested to the monastic in charge of media relations that he include it on the website, he responded, “But we’re trying to soften our image.”

The following day, before the second period of dawn zazen began, the senior monastic approached me and told me that the stick would be used. I quickly rose from my cushion and walked to the floor above. Several minutes later, I again heard the loud thwack of the stick contacting flesh, a wave of nausea and anger rising in my belly. For several breaths I tried to block out the noise. Then more cracks of the stick, resounding through the stone masonry. Finally, I stood up and climbed the stairs to the top floor of the monastery sitting before an altar to Kuan Yin, the bodhisattva of compassion, set up at the end of a hallway. Still, the noise of the kyosaku penetrated from below, sharp and sporadic as gunfire. I crouched into a ball, wrapping my arms around my legs, and tried to ride it out, my awareness retreating into a dissociative fog. For the rest of the morning I was deeply distressed, overwhelmed by sadness. Why was this happening to me? Why were my body and mind betraying me, driving me from my cushion though I knew that what was happening in the zendo was not an imminent threat?

I had to repeat an essential point to many of the people who I spoke with in the following days. Of course I knew intellectually that the use of the stick was not intended to cause harm. My response had nothing to do with intellectual understanding; it was lodged deep in my body and mind. Trauma researchers such as Bessel Van Der Kolk have written extensively about how trauma is an embodied experience. In his book The Body Keeps The Score, Van Der Kolk writes, “neurological research shows that very few psychological problems are the result of defects in understanding. When the alarm bell deep in the amygdala signals and fires the stress hormone that we are in danger, no amount of insight will silence it.” Although I was familiar with this research I was still frustrated by my trauma response, especially since I was in a monastic environment that stressed rigorous training and pushing through perceived self-imposed limits. I often felt like a failure, critically damaged in ways that kept me mired in delusion.

Dreading the next appearance of the stick in the zendo, I found myself reinforcing the very patterns of defensiveness and clinging based on the perceived separation between self and other that had brought me to practice. I thought, “No one here really knows what I’m going through so I have to take care of myself. I cannot expect the culture in this place to change for one person, so I have to protect myself and guard against being triggered.” On the other hand, I was deeply committed to staying there for the term of my residency, having gone there after speaking with my teacher about the possibility of priest ordination. She’d suggested that I find a monastery where I could engage in a period of practice longer than the seven day sesshins I’d been doing for years. My intention in venturing to the monastery was to explore monastic training and to consider what stepping into the role of a Zen priest would entail.

The day after my experience on the third and fourth floors, I had another conversation with the same senior monastic who’d proposed that solution. This time, I asked whether the use of the kyosaku could be suspended during my stay there. I explained how the noise of the stick resounded through the entire monastery and that I could not stay in the building and sit zazen. He agreed to suspend its use until the upcoming sesshin at the end of the month. During the sesshin, the encouragement stick would be used again, since, he said, “That’s what we do here.” Although I was grateful that he was willing to compromise, I question this argument. The same rationale is frequently used to justify many kinds of injustice and to silence the oppressed. Our work is to challenge such messages and to question the blind acceptance of inherited traditions. Educating ourselves in the effects of trauma will help us to do so more effectively.

Commentary about the use of the kyosaku by American Zen teachers has been sparse.In an article published over twenty years ago in Tricycle magazine called, “The Encouragement Stick: 7 Views,” a group of teachers reflect on their experience. Those who support its use do so for essentially personal reasons.As Sally Jiko Tisdale relates, “Its very sound has power for me; the sudden crack in the silent hall can turn me into a child, bring up tears and shivers, dreams. It can ring like a bell, calling me awake from across the room.” What fascinates me about her statement is that the very phenomena that triggers me, being turned “into a child’ and beset with “tears and shivers” and “dreams” is an experience that Tisdale apparently finds helpful.

Although the kyosaku has been a useful practice tool for many, it also can be traumatizing for the person who wields it as well as the person who is struck. This is reflected in the rest of Tisdale’s account which describes why she stopped using it in the zendo, as she could not stomach hitting others as they sat in zazen. The kind of vicarious trauma that she speaks of is another reason to question the use of the kyosaku. We may clearly see the potential abuse suffered by the person who is struck, but can we also envision the abuse suffered by the one doing the hitting? Is the relational dynamic that is reinforced by the act of hitting and being hit one which is ultimately conducive to our practice? If we continue to support the use of the kyosaku but cannot bring ourselves to wield it in the zendo, we are engaging in a kind of cognitive dissonance that inhibits our ability to empathize with others and to respond compassionately.

Another effect of this dissonance is that it discourages questioning, or as another person quoted in the article, Professor T. Griffith Foulk, states, “Nobody asked about the ‘meaning’ of the stick, nobody explained, and nobody complained about its use.” Since Foulk is speaking about his experience in a Rinzai temple in Japan during the seventies, the lack of explanation makes more sense. Not so in our contemporary American culture, especially in a political moment when many of us are aware that we need to diligently question how power is wielded by those in positions of authority.

As Professor Foulk notes, the tradition of the kyosaku is derived from two sources: the concept of “skillful means” that Buddhist teachers employ to help their students realize awakening, and the civil role of magistrates who would punish lawbreakers by administering blows with a stick. There is an inherent dualism grounded in the history of its use: on the one hand the kyosaku is considered a tool to bring about insight, and on the other hand it is a tool of discipline that punishes sleepiness and inattention in the zendo.

The Zen teacher Norman Fischer comments on the contradictory nature of these objectives as he explains why the San Francisco Zen Center stopped using the kyosaku in the early nineties during the first Gulf War. He says, “the kyosaku, and the samurai spirit it fostered, served to increase rather than decrease sleepiness in the zendo. It is difficult to say why this is so, but I suspect it has to do with the fact that externally imposed discipline has a deadening effect on the spirit.” The “deadening effect” that Fischer observed was what was visible on the surface; who knows what kind of trauma responses were being triggered by the stick and contributing to the feeling of spiritual malaise.

I am encouraged that the use of the kyosaku at the San Francisco Zen Center ceased in response to political events in the world. In the midst of a nation at war, a decision was made to not perpetuate an atmosphere of coercion and violence. We currently live in a country where many groups of people are traumatized daily, from immigrants held in detention centers and targeted by white supremacists to people of color assaulted and killed by police, and folks of various genders and sexual orientations attacked and denied basic rights. In this time of pandemic, we are all being traumatized in ways that will resonate long after the current crisis resolves. We no longer have a choice whether or not to work with trauma, which is another way of saying that we can no longer deny our interconnectedness, how our individual actions have profound effects on others, particularly those who are often not empowered to speak for themselves.

A few days later, I was assigned to work in what is called the dye garden, a place where some of the most physically demanding labor at the monastery occurs. Walking behind the work leader down one of the rows, I turned to say something to the person walking behind me. Suddenly, the ground beneath my left foot disappeared as I stepped into a hole, turning my ankle. After I was driven to a local urgent care center, I discovered that my ankle was severely sprained, and I was able to hobble out on crutches, returning to the monastery.

Soon, I realized that the solution that had been found to my issue with the kyosaku wouldn’t work. I could no longer leave the monastery building and walk a few hundred yards over to the sangha house. Although I regretted leaving, I bought a plane ticket back to Houston for the day before the sesshin began. Before I left, the work leader in the dye garden told me that she’d trimmed the weeds back so that people could now see the holes in the ground.

I was fortunate to be in a position where I felt empowered to express my views with the expectation that they would be heard and acknowledged. This is not the case for many practitioners whose experience with systems of power and authority has taught them to make themselves invisible, because being visible is equated with dangerous threat. Our practice places should be sanctuaries, places of safety and refuge. I hope that the kyosaku and other forms of discipline used in sanghas throughout America can be discussed openly and honestly with an awareness of how they bind and cause harm. Such conversations can transform the way that we practice.Our collective wisdom grows when we can identify our blind spots and summon the courage to make them visible.

What do you think?